Sick = Not Fun. Going to the doctor’s Part 2

I thank God SO much that we have all been kept safe and for the most part have been well while we have been here. As much as I believe medical professionals here are truly trying to do their job well, the fact remains that the system here is in many ways very different to what we are used to.

For example, doctors here are not used to being questioned, while I like to make sure I really understand what’s going on. Their attitude towards antibiotics and retro-viral drugs seems to be a bit blasé (you can buy them over the counter), but their attitude toward pain is more of a ‘tough it out’ approach (it’s almost impossible to buy codeine), and in my experience, not even cancer patients are given morphine to relieve their suffering.

Privacy as I know it doesn’t seem to factor here. I know it does seem a little strange when you think about it, but when I have an exam at the doctor’s in Melbourne they pull the curtain over and give me a little sheet to lie under to at least give me the pretence of modesty. However, here there is no curtain, no sheet but there’s a scary chair with stirrups that is opposite the doorway should anyone decide to just enter without knocking. I have had four kids and I’m probably less self-conscious than most, but even I struggle with that.

My sister-in-law recently gave birth here. I am incredibly in awe of her for braving the system, but she and my brother prayed about it and felt to have the baby here. However, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. She speaks Russian far better than I do, but she still had to deal with the hurdles of different expectations and understanding than what we are used to. And when things started to go a little hay-wire at the end as she became pre-eclamptic, it was rather a stressful time when we discovered that their protocol is quite different to that in Australia or pretty much any other western country for that matter.

Credit where credit is due, they did look after her well, and their protocol seemed to work, but I still think her a braver woman than me. She spent about 3 weeks in the hospital, where visitors are not allowed. I went to see her and had to go into a very soviet/sixties style waiting room where you can bring gifts/food and pick up washing, but do no further. If I didn’t have a mobile phone to call her on, there was a very quaint 60s style phone booth and phone I could have called her ward nurse on to send her down. If the woman is well enough she can come down to meet her visitors, but the benches are not so comfortable for a heavily pregnant woman to visit for long, and in the presence of many other people.

So, clearly there is much more than a language barrier involved. So much can get lost in translation, linguistically and culturally. And it’s clearly harder in a stressful situation.

A few weeks ago I got sicker than I have been in a long time. One of the little children from the tenements coughed directly in my face as I was holding him – a rather chronic sounding wet cough. The next day I already had a terrible headache and a raging sore throat, and then my husband had to go away for 2 weeks. Our poor guest Katie had to put up with me being miserable for her last three days (but I am ever grateful for her breakfast in bed!! After that it was fend for myself!). The Tuesday she left I got worse (see Katie, I really missed you! 😉 ) and buried my head under the pillow in denial of the things a mother still has to do even when she’s ill.

Sasha fell ill later that day, but with food poisoning. And a very bad case of it.

By Tuesday night she was running a high temperature and running to the bathroom. I didn’t sleep much trying to keep her temp down and her hydration up. Neither or us felt like we could surface from bed and the other kids had to pretty much manage for themselves as I tried to organise them to get groceries and make their food while just wanting to curl up at my mum’s and feel her TLC.

Wednesday was tough, with no improvement in either of us and my voice had finally disappeared. By Thursday morning I was really concerned about Sasha. At 4.45am I gave her paracetamol and at 6.45am ibuprofen, but by 7.15am her temperature was still about 40C and she was very weak and in a lot of pain. I felt incredibly far from home and scared. If I were in Melbourne I would have taken her to the ER, but I wasn’t. She was too sick to take to the doctor, so at 7.15 in the morning I called the ambulance service, which doubles as a call out doctor, to come to our flat. No easy feat given I could barely speak above a whisper and the phone operator spoke so fast I struggled to understand her.

Technically we are not eligible as we don’t have a local policy, but they treated her anyway. For that I am truly grateful. There are some good things about Russia and their ‘follow the rules when it suits’ approach to life.

They arrived very quickly, but the experience was a bit overwhelming.

I answered the door to a lady doctor (actually, they’re just about all female doctors here, interestingly) who waltzed in and asked where the patient was. I was a little surprised and taken aback as after living herу for a while I have become very accustomed to the fact that you always take your shoes off when entering someone’s home. But she just walked straight on in.

I figured that the service is called “fast help” for a reason, and showed her through.

I explained what was going on, and that Sasha doesn’t speak Russian. No matter. The doctor just proceeded to speak louder at her. Even when Sasha explained that bright light and loud noises made her head hurt, she spoke louder. Remember this when dealing with migrants, speaking louder doesn’t make you any more intelligible…

The doctor suggested it would be best to go to hospital. Both Sasha and I felt horrified at the thought, and I think the doctor saw my face as she asked whether we’d prefer to treat her at home. She said that she would get another doctor from the children’s polyclinic to come out later, and that we’d need a stool sample taken as soon as possible because the next day was a public holiday and then it would be the weekend. She could give an injection for the pain and the temperature. In the bum.

In Sasha’s fragile state she found this incredibly overwhelming and scary and became quite teary. The doctor’s approach was very much, “Well, does she want the injection or not?!? I have other patients to get to!”

Actually, I don’t feel angry with the doctor, just sad that this is the state of affairs. Although I have met VERY MANY really lovely, kind and considerate people here, this kind of attitude is sadly not unusual. And to be fair, doctors here usually get paid VERY little, and she probably really was in a hurry. Russian kids are usually much more stoic than our kids have been brought up to be and she probably wasn’t impressed with Sasha’s reaction.

So she had the injection, and it hurt, but it worked.

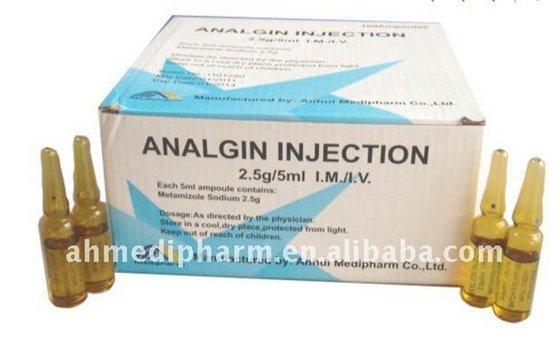

I had tried asking the doctor what it was, but she was in no mood to entertain my questions. Nor did she ask any questions regarding Sasha’s medical history before giving it. At that point in time I was fairly desperate and decided I needed to trust her, but I also decided to look up the medication after the fact.

The medication’s name is Metamizole (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metamizole), more commonly known here as Analgin. It is quite widely used in Russia, and available in over the counter preparations. It is very effective at reducing temperature and provides quite reasonable pain relief. It has also been completely banned in Australia, the US and a number of other countries, and heavily restricted in others due to the high risk of toxicity. One possible risk is anaphylaxis in patients with a history of asthma. The doctor never asked. She gave the injection and went.

Sasha has a history of asthma. Thank you God for your protection.

Later that day the children’s doctor came. She was the complete opposite of the first doctor. She was clearly past retirement age, small, stooped and slow. When I opened the door I ushered her straight in to where Sasha lay, but she stood her ground by the door and asked where she was supposed to hang her coat up. I’d forgotten my manners already!

I invited her in again, but then she asked me to get plastic bags to put over her shoes. I told her not to worry, to come straight in, but she insisted. So I found some plastic bags and lead her to Sasha. She stopped again and looked at me as if I were a simpleton and asked where the bathroom was so she could wash her hands. Why hadn’t I thought of that? The first doctor hadn’t. I felt very disorientated and needed to lie down myself.

Finally we made it the ten metres from the front door to Sasha, whereupon the doctor stood and looked at me again with that, you’re-really-not-with-it-are-you? face, and asked me to get her a chair. She asked me what was wrong, I told her. She poked Sasha’s stomach a few times, asked me for a spoon to use as a tongue depressor and then looked at Sasha’s throat. She then told her to stand up, turn around, bend over, before handing me a swab and telling me to take it!

Next, I had to find paper and a pen (the government clearly, really does provide very little money for health!) and she wrote a string of instructions and a long list of medications I needed to buy. I felt really bad that I didn’t understand all of them very well and she had to repeat them. Apparently we were too late to get in a stool sample as they only take them between 8-11 in the morning and it would be Monday before we could take it in, so she told us where to go the next week and when, but I was really confused about whether she was talking of the sample or an appointment. (When Sasha started to improve, we just decided to skip the follow up, it seemed easier!)

This doctor too was very keen to get out the door because her ride was waiting. I felt so bad because it appears she ended up missing it and had to walk slowly the kilometre and a half back to the clinic. I hope the handful of chocolates we gave her helped a little :/

As sick as I felt, I headed to the chemist. After researching, I decided to drop one of the antibiotics, but loaded up with antibiotics, prebiotics, probiotics – and chamomile tea! If that’s one thing they’re really good with here, it’s the notion of populating our gut with the right kind of flora. We were set.

Thank God that the antibiotics did the trick, and Sasha gradually improved over the next 10 days, but it was a very scary experience. Having to deal with the system all on my own, while feeling sick and fragile myself and Nickolai being away, was exhausting and daunting. I started wondering what I would do had things been any worse. I also started realising just how much we have placed ourselves in God’s hands, and how very little control we really have over our lives. I started thinking how I would feel if the health system here was my only real option, and not the wonderful system we have in Australia. How much of it is actually unacceptable, or is it more just about a different culture? And which parts do I just need to learn to accept? I’m still working it out.

And this time, it’s time for some chamomile tea…